I’ve been following the international March of Science movement with great interest. Not so much because I’m overly worried about war on science, alternative facts gaining ground or post-truth times. I can see why these are burning issues right now especially in the US, but I think in Europe we’re still mostly okay. I am interested, however, in how science and policy-making interact especially in environmental decision-making and so I’ve been more curious of how the core principles of the Science March (most notably “evidence-based policy and regulations in the public interest”) and the goals (“partnering with the public” and “affirming science as a democratic value”) are framed and discussed either in the march events around the globe or in the discussions surrounding the events.

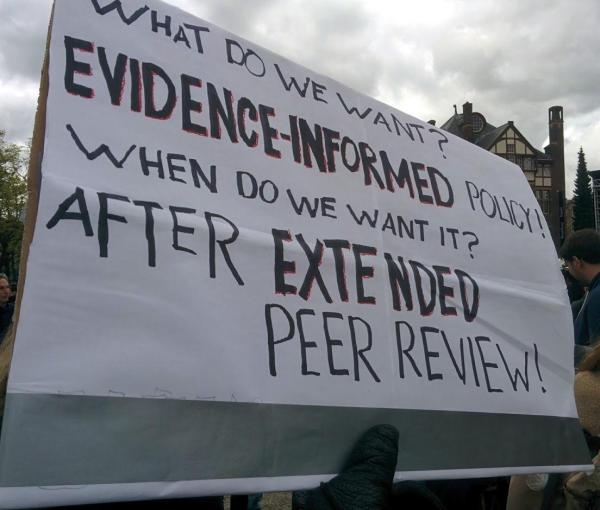

The topic is highly relevant for my own work; spatial conservation planning and decision-analysis is highly context-dependent and understanding how those contexts come about is important. Since the birding trip out to Texel island we were planning for this weekend was postponed, I got a chance to join the March of Science organized here in Amsterdam. If nothing else, I’d get to make a sign! Here’s the sign I came up with:

In this post, I will explain in more detail why I chose to march [1] with this sign.

Evidence-based policy and regulations

Despite the countless studies in policy science and the volumes of pages written about the topic, somehow the science marcher below captures how many scientists seem to view the relationship between science and policy (or science communication more generally):

#marchforscience pic.twitter.com/mLyTXUG3Sl

— Lisa Hawke (@lisadmh2) April 22, 2017

That sign right there nicely captures the called the information deficit model, according to which public skepticism to science and poor public decision making both mostly stem from lack scientific information. Hence, providing more and better information is the solution to both issues. This model has been discredited time and again, but somehow it still is very popular especially among natural scientists. Unfortunately just providing more information and facts does not usually change people’s minds nor lead to better public decisions [2]. Like it or not, real-life policy-making is messy, iterative, often unstructured and affected by myriad values, worldviews and biases that make us human. In this type of setting, it’s everything but clear how exactly science is supposed to help. Even more depressingly and relating to my own field of environmental science, Daniel Sarewitz has made a compelling case for “how science makes environmental controversies worse”.

This brings us to one of the core principles of the Science March (and my sign): evidence-based policy and regulations in the public interest. First about that public interest. If there was any doubt that the March and its goals are not political, this alone should put those doubts to rest: anything dealing with the deliberation of public interest is thoroughly and undeniably political, as it should be. While some, especially in the US, have raised concerns that the politicization of science may be counter-productive for the goals of the March, politicization is hardly an issue if one accepts that science is already deeply enmeshed with politics. Instead it seems like scientists are not being political enough. Andrew Jewett has already written a much more articulate and thoughtful piece on the matter than I ever could, so I’ll just leave this quote here:

“My concern is the opposite of the usual objection. The March for Science, I believe, is not political enough. I do not mean that the marchers should campaign for Democratic or Republican candidates or take stands on contentious issues such as immigration reform. Rather, I hope that they will come to grasp much more clearly how political power works, how it intersects with social conflicts, and how policies emerge from this nexus.”

Replace “Democrats” and “Republicans” with whatever political parties govern your country, but the message remains the same: understanding how policies emerge from the complex socio-political nexus is crucial. In particular when we’re talking about evidence-based policies. Why? Because evidence and policies too are deeply connected. Acknowledging that “evidence-based policy” is vague term with multiple interpretations, to me it still conveys the idea that there exist a body of (factual) evidence separate from the vagaries of policy-making [2]. This evidence can then be used as basis of rational policies and everyone goes home happy. In the context of evidence-based conservation, again closer to my own field of work, Adams and Sandbrook have critiqued (behind a paywall) evidence-based conservation on the following grounds:

- It can be policy prescriptive (“disguising the politics of decisions in a fog of apparently technical issues”)

- It promotes some type of evidence (quantitative) on the expense of other (qualitative)

- It supports the linear model of decision-making, in which good information fed in at one end leads to good decisions at the other (see the information deficit model above)

- It presents itself as politically neutral, whereas evidence is never neutral (it never “speaks for itself”)

Instead, they promote “evidence-informed” decision-making, which takes a broader view on what counts as “evidence” for policymakers and accepts that “many decisions are, and should be, deliberative, and not based in any automatic way on scientific evidence”. This is not to say that anything goes and that robust scientific evidence wouldn’t be useful and sometimes even preferred. It does mean, however, that science doesn’t have a monopoly in providing evidence for decision-making. I too firmly believe that science has a indispensable role in informing public policies. I also believe that without a deeper understanding of the policy processes evidence is supposed to inform, evidence alone will not save the day.

Fortress science

Now, I don’t honestly think that anyone is suggesting a technocratic monopoly on evidence production for science even on a Science March. Or are they?

know your role. thx.#EarthDay #marchforscience pic.twitter.com/Sqvsb4p78S

— Matt Rainone (@Matt_Rainone) April 22, 2017

Fair enough, pulling random tweets from the internet is not exactly investigative journalism, but I don’t think this is an isolated incident. Take for example Neil deGrasse Tyson, the Carl Sagan of our times in making science known among the broad public. In this video, shared a lot in social media lately, he asserts the following:

“I choose not to believe E = mc^2” You don’t have that option. When you have an established scientific emergent truth it is true, whether or not you believe in it. And sooner you understand that, the faster we can get on with the political converstations about how to solve the problems that face us.”

Tyson’s positivist notion on objective emergent truths may work well for things such mass-energy equivalence, but less so for complicated wicked problems, such as many environmental issues [4]. More to the point, in both cases science is given the authority to define what the problems are after which the potential solutions can be politically debated. Problems identified by science, however, should not be subjected to political debate. This authority is further bolstered by the fact that scientists themselves decide what constitutes legitimate science through the process of peer review.

In practice, what separates science from non-science is the formal process of and acceptance through peer review. The process looks a bit different in different fields of science each with their own paradigms and social conventions. In natural sciences, for example, you come up with a question, form a hypothesis on what the answer might look like, design and execute an experiment that can falsify your hypothesis, and if you can’t falsify the hypothesis, conclude that there is reasonable evidence to support your hypothesis.

However, professionally your conclusions account to almost nothing unless your work can pass through peer review typically organized by a scientific journal to which the work is submitted to. At least a journal editor and 2-5 (usually) anonymous scientists having expertise in - or at least familiarity with - your field have to be convinced that you have done sound science and that the findings are novel enough to merit publication [5]. In case your work passes the peer review process, it gets published and joins the ranks of established science.

Given the immense authority that peer review enjoys as the arbiter of legitimate science, I was surprised to find out that the current peer review system was widely adopted as late as 1970s. Whether or not peer-review actually deserves its status as the sole mechanism of scientific quality control is one thing, but what is clear is that scientific community reserves all rights to decide what is and what isn’t considered legitimate scientific information. All this means not only that scientifically identified problems should not be subject to political debate, but also that science gets to decide what potential (scientific) solutions are considered. Science is not so much an ivory tower, but a fortress with its gates vigorously guarded.

Extended peer review

So what’s wrong with all this? Surely objectivity can only be guaranteed through an independent and rigorous scientific process? The problem - especially in decision-making context - is that science doesn’t have an opinion which problems to study; scientists do. If we accept the fundamental connection between science and politics, then separating the two is impossible and having unelected experts affecting the policy process becomes problematic, especially in a regulatory context. Against this backdrop, the War on Science in the US can be seen as not a war on reason and facts, but as a Conservative war on a particular type of government. Similarly, the March of Science has already been portrayed as nothing more than part the ongoing Left’s political narrative and agenda [6].

I find the idea of contesting political views much less worrying than contesting reason itself. Could our current peer review system be developed to account not only for professional expertise, but a broader set of knowledge and values as well? Extended peer review is an idea formulated by Functowicz and Ravetz in the contex of post-normal science. When uncertainty and decision stakes are high - as is the case with many environmental problems - professional peer review isn’t necessarily a sufficient guarantee for scientific quality. Involving a “extended peer community” brings multiple knowledge systems, including traditional and tacit knowledge, into the process thus potentially increasing the reliability and applicability of the results. The latter is achieved through increased trust among participants leading to higher relevance and legitimacy of the whole process. That’s the theory, at least.

It’s of course possible, even likely, that involving a broader stakeholder group in the peer view process will introduce many different types of biases potentially compromising the scientific credibility of the whole approach. This can be partly mitigated by a requirement of high reflexivity, i.e. transparency and articulation of interests and values each participant holds [7]. Whether or not such extended peer review would work depends on many factors I’m sure, but it’s already seeing action for example in the EKLIPSE Knowledge and Learning mechanism. In any case, it’s clear that partnering with the public and affirming science as a democratic value means changes more profound than increased science communication and outreach. As Peter Gluckman, the chief science advisor to the PM of New Zealand, put it:

“The social contract between science and society must be constantly renewed, recognising the evolution in both the nature of science and the society in which it is embedded. In short, society has a stake in what science is done, how it is done and how it is applied. Concepts of knowledge co-production, co-design and extended peer review flow from such recognition and the science community will need to engage more with these emerging concepts and practices.”

That’s why extended peer review made it to my sign.

So, why I marched?

In the end, perhaps it’s less about “the Truth” and more about power politics, including who are the winners and losers of any given set of facts we choose to follow in public policy-making. How do we collectively navigate the turbid waters of such power politics remains to be seen, but acknowledging that this is in fact what we are facing is a start. It could also be that I’m just coming up with one straw man after another and most things I’ve discussed in this post are well-known in the scientific community. Or that the ideas presented above are pushing us too much into the domain of postmodern epistemic relativism. If not, I think it’s important that these topics are discussed more broadly. That’s why I went to the science march. Not that there actually was much discussion about these issues in the event, but at least it gave me an opportunity for valuable self-reflection. Hopefully rougher seas for scientists also means that more scientists along with other members of the civil society will start thinking about the role of science in our democratic societies. If the March of Science achieved to do that for some, I think it was worth the effort.

[1] There actually wasn’t any marching, so science standing might be more apt.

[2] See pretty much anything from Dan Kahan and the Cultural Cognition project

[3] See e.g. Paul Cairney’s book The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making.

[5] I dare not say “climate change”, although this is clearly what Tyson is implying in the video as well.

[5] The latter is peculiar (non-)criteria for science, but must wait for another blog post.

[6] Again, this is all in the US in which the extreme polarization of the two-party system probably makes things worse. In Europe, the situation calls for less war-like language.

[7] See also Jasanoff’s “Technologies of humility: Citizen participation in governing science” http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025557512320